Sanctions and Humanitarian Action in Syria

7 September 2021Sanctions are a wide range of measures that aim to influence behaviour without involving the use of armed force. This fact sheet provides an overview of how sanctions work, and how they can affect humanitarian action, specifically in the context of the conflict in Syria.

1. How do sanctions work?

Sanctions are a wide range of measures adopted by the UN, regional organisations, such as the EU, and individual states that aim to influence the behaviour of other states, individuals or groups without involving the use of armed force.

Sanctions are permissible, but must not violate other rules of public international law. They should be crafted so as to have maximum impact on those whose behaviour they aim to influence, and to reduce adverse humanitarian effects or unintended consequences for persons not targeted.

2. Who imposes sanctions?

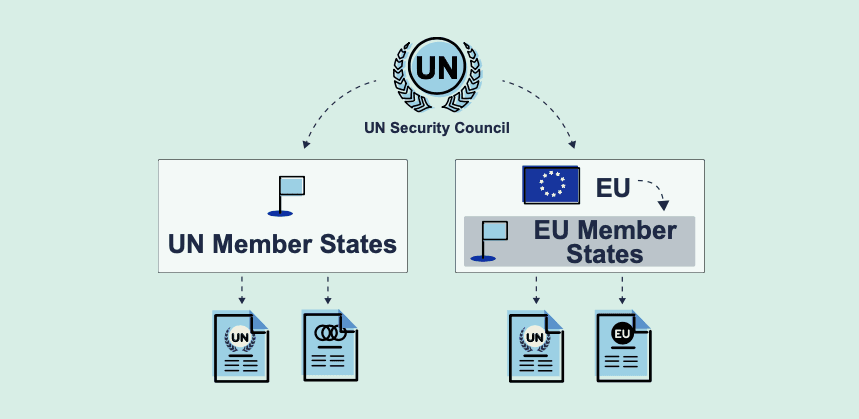

A number of different actors can impose sanctions.

The UN Security Council, acting under Chapter VII of the UN Charter, can adopt sanctions. These are binding on all UN member states, which must give effect to them in national law.

The EU gives effect to UN sanctions for EU member states. In addition, it can adopt its own ‘autonomous’ sanctions. These can:

- impose additional restrictions to those adopted UN;

- designate additional persons;

- apply in situations where the UN has not adopted sanctions.

UN and EU sanctions are implemented by states. They adopt the necessary laws and measures at domestic level, grant licences/authorisations, and enforce the sanctions. They may also adopt additional autonomous sanctions.

3. What is the objective of sanctions? And how do they seek to achieve it?

Sanctions seek to bring about a change in the policy or conduct of the persons or groups they target. These objectives could be preserving peace, ending conflicts, promoting compliance with human rights and international humanitarian law, or fighting terrorism.

Sanctions aim to achieve these objectives by imposing various restrictions on the people or groups whose behaviour they seek to change. These include:

- embargoes on the provision of weapons or of equipment that could be used for internal repression;

- other export restrictions;

- restrictions on admission i.e. ‘travel’ bans;

- financial sanctions that prohibit making funds and assets available.

The restrictions are imposed on ‘listed’ or ‘designated’ people or entities. Usually these are:

- heads of governments and ministers;

- entities, including companies, that provide the means to conduct the targeted policies;

- groups or organisations, such as organised armed groups or terrorist groups;

- individuals supporting the policies the sanctions are trying to modify.

UN and EU sanctions aim to be ‘smart’ or ‘targeted’ i.e., have an adverse effect just on the leadership figures whose behaviour they aim to change. Unilateral measures adopted by some states are broader in scope, and more akin to the comprehensive sanctions on countries that the international community moved away from in the 1990s because of their indiscriminate effects.

4. Which sanctions must NGOs comply with?

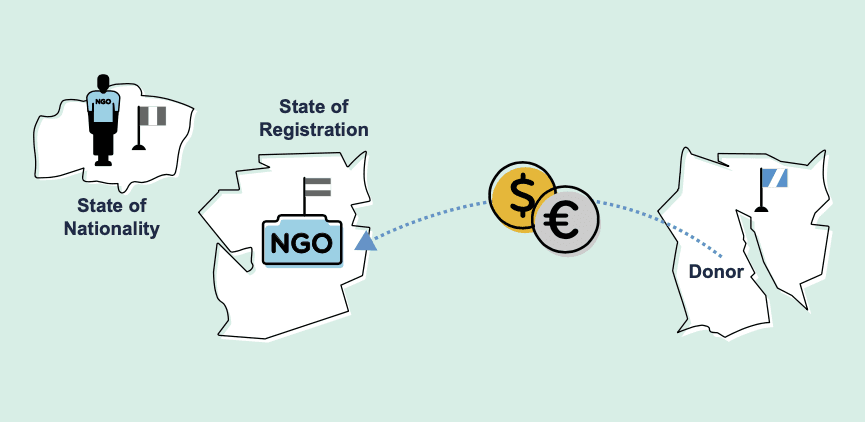

NGOs and their staff are likely to have to comply with the sanctions adopted by a number of different states.

Some sanctions are directly applicable to them. These include:

- the sanctions adopted by the NGOs’ state of registration — and NGOs may be registered in more than one state;

- the staff of NGOs must also comply with the sanctions adopted by their state of nationality. This does not render these states’ sanctions applicable to the NGOs, though. Additionally, states’ funding agreements frequently require recipients to comply with the sanctions adopted by that state. In this way the donor state’s sanctions become indirectly applicable to the recipient, via the agreement that NGOs conclude with donors.

5. How can sanctions affect humanitarian action?

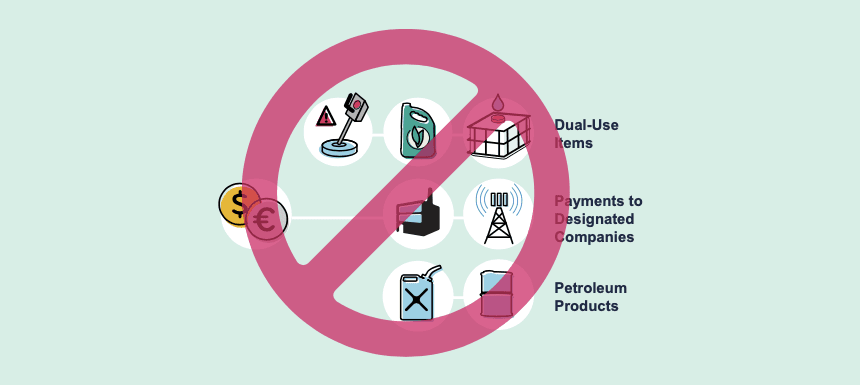

Restrictions in sanctions can affect humanitarian action in a number of ways.

- Restrictions on imports of dual-use items may cover items or materials that humanitarian actors need for their operations, in areas such as water purification, agriculture and even medical response.

- Incidental payments that humanitarian actors may have to make in order to operate may fall within the prohibition in financial sanctions on making funds or other assets available to designated groups.

- Commercial companies whose services humanitarian actors may require for their operations — e.g., telecommunications providers — may be designated and subject to financial sanctions prohibiting making funds available to them.

- Sanctions may impose restrictions in trade in certain commodities, like the prohibition on purchase of petroleum products in EU Syria sanctions.

Broader sanctions, such as those imposed by the US, may preclude many forms of support to the government of the state in question, prohibiting the provision of assets and support to ministries and departments responsible for meeting basic needs, such as the ministries of health and education.

6. How can the tensions between sanctions and humanitarian action be reduced?

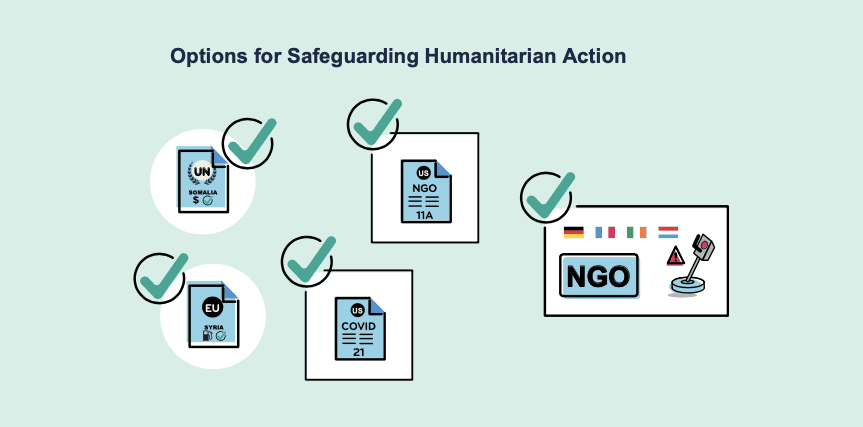

There are a number of ways sanctions can safeguard humanitarian action.

- Exclusion of humanitarian action from the scope of the prohibitions — e.g., financial sanctions in UN Somalia sanctions;

- Exclusion of certain humanitarian actors from the prohibitions — e.g., humanitarian actors receiving funding from the EU or EU member states in the EU Syria petroleum sanctions;

- General licences for certain humanitarian actors to carry out certain otherwise prohibited activities — e.g., US Syria General License 11A — or for particular activities to be conducted — e.g., US Syria General License 21;

- Possibility for humanitarian actors to apply for specific licences/authorisations to carry out otherwise prohibited activities — e.g., import of dual-use items under EU Syria sanctions.

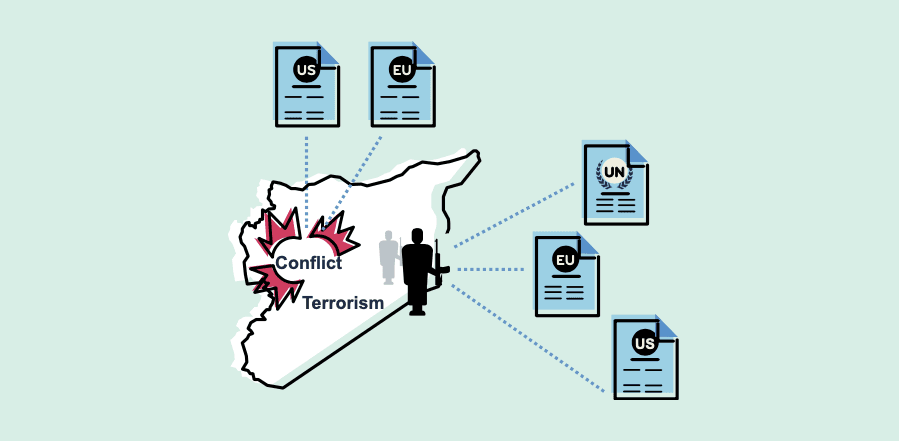

7. Sanctions imposed in relation to Syria

Humanitarian action in Syria is affected by sanctions imposed for two principal purposes:

- Sanctions imposed by the EU and the US — including the Caesar Act — in response to the conflict since 2011, to end the conflict and promote compliance with international humanitarian law and human rights. The UN has not imposed conflict-related sanctions.

- Sanctions imposed by the UN, the EU and individual states on groups designated as terrorist operating in the territory of Syria including most notably, ISIL (Da’esh), Al-Qaida and affiliates. In Syria, these groups include ISIS, and Al-Nusra Front/Jabhat Fateh al-Sham/Hayat Tahrir al-Sham.

8. A closer look at US measures

US Sanctions

Since 2011, the US has imposed broad sanctions in relation to the conflict in Syria. The key restrictions of relevance to humanitarian actors are:

- A prohibition of making any contribution or provision of funds, goods and services to or for the benefit of any designated person or entity;

- Except as otherwise authorised, a prohibition on export or re-export, sale, supply directly or indirectly of any services to Syria;

- Except as otherwise authorised, a prohibition on purchase of petroleum products of Syrian origin;

- Unless specifically authorised, a prohibition on making charitable contributions of funds, goods, services or technology including to alleviate human suffering such as food, clothing or medicine for the benefit of the Government of Syria or any other designated entity.

Who, of relevance to humanitarian action, is designated under these sanctions?

- The Government of Syria. This is defined very broadly, and includes ‘the state and the Government of the Syrian Arab Republic, as well as any political subdivision, agency, or instrumentality thereof, including the Central Bank of Syria’;

- Commercial entities with whom humanitarian actors may have to conduct transactions, such as Syriatel and Cham Airlines.

Are there any exceptions?

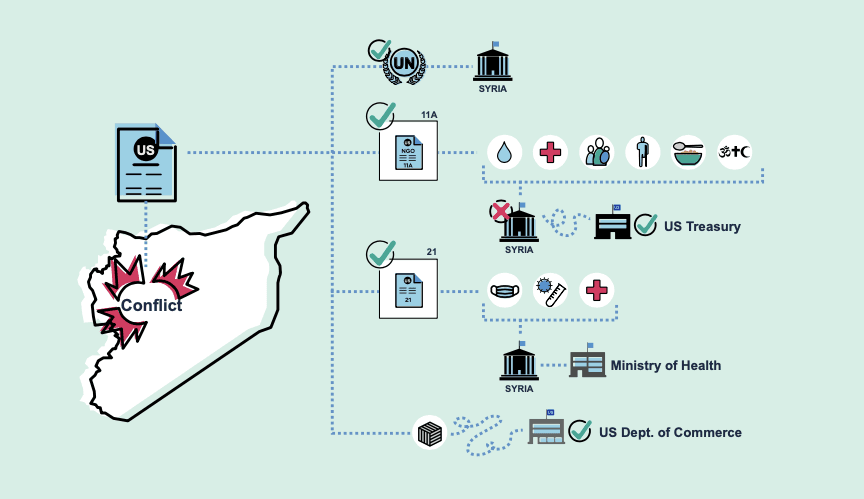

Different possibilities exist, depending on who is conducting the humanitarian operations and the activities involved:

- Activities of UN agencies that entail otherwise prohibited transactions or activities with the Government of Syria are authorised. NGOs fall within the scope of this exception only if they are 100% funded by the UN.

- General License 11 A authorises some activities by NGOs, including activities to support humanitarian projects to meet basic human needs in Syria, such as drought relief, assistance to refugees, internally displaced persons, and conflict victims, food and medicine distribution, and the provision of health services. It does not authorise the provision of services or charitable donations to the Government of Syria.

- Specific licenses are required for such transactions with the Government of Syria. They may be issued by the Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) in the Treasury Department on a case-by-case basis. However, procedures for applying for specific licences are notoriously slow and applications for similar transactions appear to have been treated inconsistently.

- In July 2021 OFAC issued General License 21. This authorises: the export to Syria of services related to the prevention, diagnosis, or treatment of COVID-19; the conduct of COVID-19-related transactions and activities related to the prevention, diagnosis, or treatment of COVID-19 with certain listed persons, including the Government of Syria.

US export restrictions

In addition, export licences from the Bureau of Industry and Security in the Department of Commerce (BIS) are required for the export of goods other than food and medicine.

This is a different and additional process from applying for specific licences from the Department of Treasury.

Export licences are required for medical devices and technology such as computers and software needed for home schooling during COVID-19 lockdowns that contain more than 10% of US components.

Export licence applications to Syria are subject to a general policy of denial. Applications may nonetheless be considered on a case-by-case basis for:

- medical devices;

- telecommunications equipment and associated computers and software and technology;

- items in support of UN operations in Syria, or items necessary for the support of the Syrian people including items related to water supply and sanitation, agricultural production and food processing, power generation, construction and engineering, transportation and educational infrastructure.

What does this mean for humanitarian actors?

Obtaining export licences is an additional procedure to applying for specific licences in relation to financial sanctions from OFAC. The two processes are not connected. Obtaining export licences is complex and time consuming.

9. A closer look at EU sanctions

The EU’s Syria sanctions are far more targeted than those adopted by the US. In particular, they do not include prohibitions on the provision of support to

the Government.

But they include restrictions that can affect humanitarian action such as:

- Purchase of petroleum products. There is an exception for humanitarian actors that receive funding from the EU or EU Member States. Other humanitarian actors must seek authorisation from Member States.

- Materials necessary for COVID-19 response (e.g., certain types of PPE or disinfection materials) or for other operations are on dual-use item lists. Their import requires authorisation from Member States.

- Entities with whom humanitarian actors need to conduct commercial transactions may be designated (e.g., telecommunication providers whose services are necessary for continuity of education during lockdown).

Although not prohibited, all these activities must be authorised by Member States. Procedures for obtaining authorisations are complex and slow and differ between the 27 Member States. In May 2020, the European Commission issued guidance on its Syria sanctions. These included three points of particular relevance to humanitarian actors in Syria and elsewhere:

- ‘in accordance with International Humanitarian Law where no other option is available, the provision of humanitarian aid should not be prevented by EU restrictive measures’. This recognises that humanitarian assistance takes priority over any inconsistent restrictions in sanctions.

- Sanctions do not require the screening of final beneficiaries of humanitarian programmes. Once someone has been identified as an individual falling under humanitarian principles, no further screening is required.

- Member States are responsible for the implementation of sanctions, including the granting of authorisations, and are encouraged to adopt a number of measures to expedite such processes, including suggesting that states could issue a single authorisation for the provision of humanitarian aid to respond to the COVID pandemic.